In the last post we started to discuss the search options for the advanced search screen of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website at www.cwgc.org. We discussed ways to search on Surname and Forename, so please do have a look at the last post. Let us take a closer look at some of the other search options and what they mean for your searches, and why you may want to use them.

Country – use this if you know where your ancestor is commemorated. France is not a good choice as there is hundreds of thousands who died there. But if you know that your ancestor died and is commemorated in Argentina, then you are in luck as there is only two options.

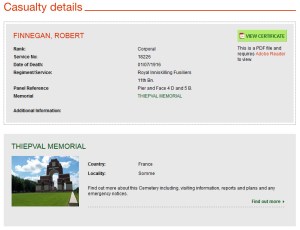

Cemetery or memorial – this is useful if you want to get a sense of context, or possibly see who else might be remembered in that location. If you start to type a place and there are multiple options a list will appear. For example, searching on Thiepval brings up four options, selecting Thiepval Memorial and searching on that location shows that 72,338 individuals are memorialized on this one memorial. These are the people for whom no identifiable remains were located to be buried. Corporal Robert Finnegan discussed in the last post is one soldier named on Pier 4D, face 5B.

War – this limits your choice to the First or Second World War

Date of Death – starting and ending – allows you to define a period in which your ancestor died, or to determine how many others died on a given day, possibly indicating if he died in a major battle or in a quiet time. For example, a search for the names of those who died on the 1 July 1916 names 18,708 individuals and obviously does not include those who died from their wounds over the following days. This was the worst day in British military history if you did not already know that.

Served with – lists the forces of the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, India and South Africa. Be very cautious here as people from the United Kingdom may have served in any of the colonial forces, and many from the colonies did serve in the United Kingdom forces.

Served in – identifies the branch of service – army, air force, navy, merchant navy, civilian war dead and miscellaneous. The last category may need some clarification for this includes: munition workers, Red Cross members, Voluntary Aid Detachments, canteen workers, army cadets, ambulance drivers, war correspondents, etc.

Rank – as you start to type in this field a list of options appears from which to choose.

Service number – this search may be useful if you have this number from another source, such as a medal roll and want to identify where he is buried or memorialized.

Regiment – can be used to narrow a search, or used with dates to put a death into context. Again when you start to type a list of options appears. For example, searching on the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers for the 1 July 1916 shows that there were 833 deaths in this one regiment alone on this day.

Secondary Regiment – should be used with caution as the majority of records contain nothing in this field.

Awards – this enables you to identify those individuals who were awarded a medal (such as the Victoria Cross), or were Mentioned in Dispatches. Returning to the 1 July 1916, with the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, and identifying Victoria Cross recipients we identify Eric Norman Frankland Bell of the 9th Battalion. The descriptive citation is provided, adding more color to the day Robert Finnegan died, for the 9th Battalion preceded the 11th Battalion out of the trenches moving towards the German lines.

Additional Information – can be any term but it would need to appear in the additional information part of the database. It might, for example, be used to identify others from your ancestor’s village or street.

There is a lot of material in this database and some experimenting with the search options will narrow your options to find your ancestor, at the same time additional information can be gleaned to put your ancestor into context.

I’m pleased to announce that copies of my latest book – Discover English Parish Registers are now available in both print and electronic formats. It is published by Australian publisher Unlock the Past. You can purchase the

I’m pleased to announce that copies of my latest book – Discover English Parish Registers are now available in both print and electronic formats. It is published by Australian publisher Unlock the Past. You can purchase the